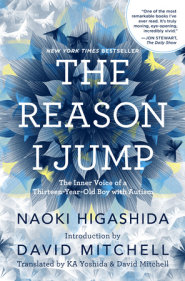

Unfortunately for those on the autism spectrum, it is not as easy to replicate their experiences for those who are neurotypical. The communication difficulties that people on the spectrum experience often prevents the most severely affected from even describing how they experience the world. However, advances in technology and understanding are helping to close the gap. One result is The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida and translated by KA Yoshida and David Mitchell.

Higashida, who was diagnosed with autism when he was five, has little access to communication through speech. However, through the perseverance of an educator and his mother it was discovered that he could communicate through the use of an alphabet grid. At first a caregiver would translate this pecking into sentences, but now it is accomplished more efficiently through a computer. The wall between the autistic and physical worlds was broken.

In the The Reason I Jump, Higashida invites the reader to “a nice trip through our world.” However, as the father of two autistic daughters, I did not always find the reading to be pleasant. A recurring theme throughout the book is the deep sadness the author felt at not being able to please his caregivers. He would often know what was expected of him but could not get his mind or his body to conform. It was a harsh reminder that no matter how frustrating it may be to care for someone who is on the autism spectrum, it is nothing compared to living on the spectrum.

Thankfully, the book does offer practical solutions for improving relationships. For example, under the heading of “Q14 Why do you ignore us when we’re talking to you?,” the author explains that he does not always recognize that someone is talking to him and that this is not the same as deliberately ignoring. His simple solution is that it “would help us a great deal if you could just use our names first to get our attention before you start talking to us.” Under “Q53 Why are you obsessive about certain things?” he explains that it is in response to a need and makes one simple request. “When our obsessive behavior isn’t actually bothering anyone, I’d ask you just to keep a quiet eye on us.” In situations where these behaviors must be stopped, he says “we may well make a terrible song and dance about it, but in time we’ll get used to the idea. And until we reach that point, we’d like you to stick with it, and stick with us.”

I found hope in the fact that Higashida has indeed found the “special” in “special needs.” He says at one point that given the option to wipe away his autism he might not take it. “But so long as we can learn to love ourselves, I’m not sure how much it matters whether we’re normal or autistic.” In another he explains the detail in which autistic people experience the world and how they have the ability to see the unique beauty of every object. Wouldn’t we all like to break free of our constraints and jump until we feel lighter as if we could “change into a bird and fly off to some faraway place.”